Why my career is like E. coli

The benefits of staggering periods of execution and exploration in work

You’ve probably heard this advice before: don’t leave your current job until you’ve already found your next one. I still can hear my father booming down from his living room recliner when I told him I was quitting my first job out of college: “What are you a fool? You don’t just up and quit. You only leave when you’ve already got the next job lined up.”

I knew my dad offered his advice with the best of intentions. He was worried I’d end up unemployed (or even worse, unemployable). You see, back in his generation, having a job meant stability, value, and respect. Being jobless was a mark of dishonor – a sign that you didn’t have anything that employers wanted. It was OK to change jobs occasionally, but you always lined up the new job before leaving the current one – otherwise you’d be setting yourself up for failure.

But what my father didn’t realize was that while my first job as a management consultant provided a good salary and was a valuable apprenticeship in the business world, it also came with a lot of stress and anxiety. I had no free time. I was working so hard that my meals alternated between dollar pizza, peanut-butter crackers, and frozen Trader Joe’s pasta. My weekends had two goals: catching up on lost sleep, and catching up on work I was supposed to have completed the week before. Working in this way posed a dilemma – while a steady paycheck provided me with a sense of comfort, how was I supposed to figure out what I really wanted to do in life if all my time and attention was focused on the job supplying that paycheck? Or more succinctly: how can one focus on happiness if one is preoccupied with survival?

Well, it turns out that the natural world has a solution to this career problem, and it lies in one of the most unexpected places: the doodles I took in my AP biology notebook.

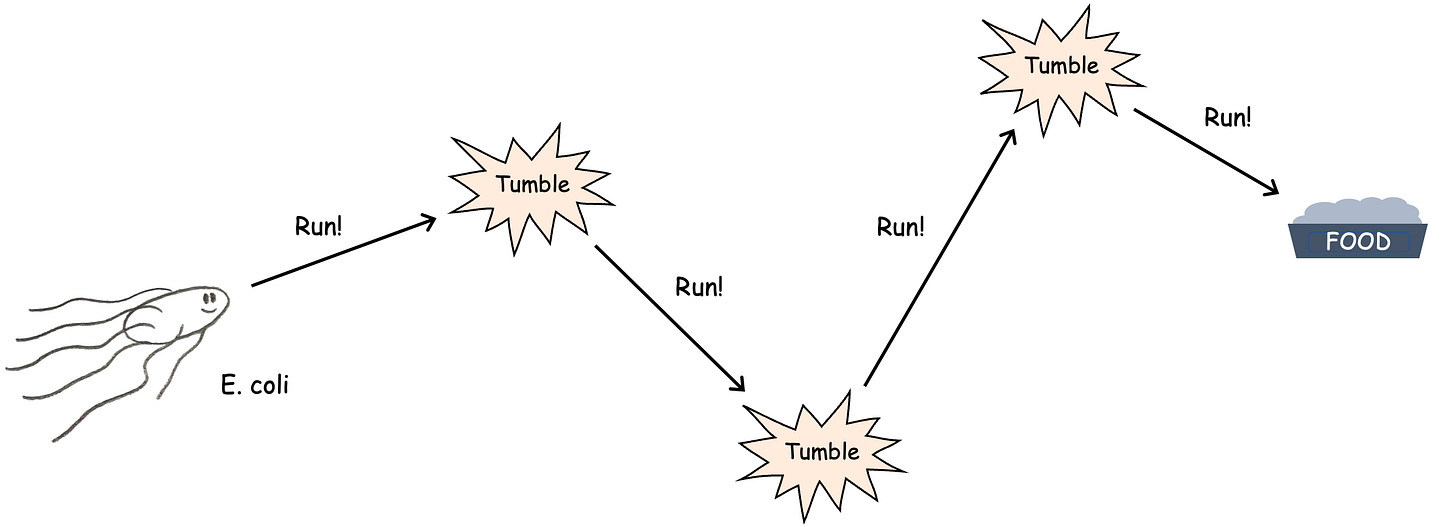

Many of you are probably familiar with bacteria from high school. These little organisms, despite being just one cell, are quite resourceful. In fact, one of the most common bacteria in the world, E. coli, has a clever way of finding food. It first senses the general direction of food, and then it rotates its flagella (whip-like structures) to shoot off more-or-less towards it ("running"). After doing this for a while, when it realizes that it’s not perfectly on target, it stops, lets its flagella flail about randomly, and re-orients itself toward the food ("tumbling"). It then starts running again, more accurately toward the food. It's through this iterative process of "tumble and run" that E. coli achieves its goal.

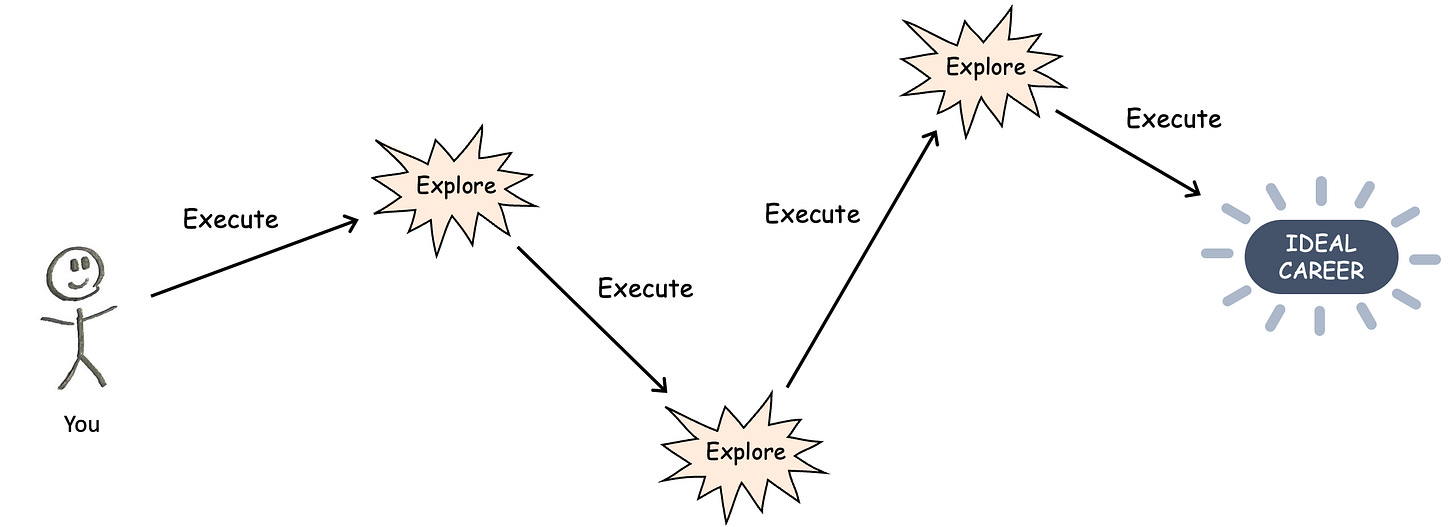

So then, how in the world does the behavior of bacteria relate to anyone's career? Consider this: E. coli has learned that simply driving forward at full speed isn't enough to reach a valuable destination. That's why it periodically tumbles – it pauses, assesses, and reorients itself. This secondary, evaluation mode helps it figure out if it’s on-track or off-track. In a parallel sense, I realized I could adopt a similar "two-mode" approach for my career, alternating between running (“execution mode”), and tumbling (“exploration mode”).

In execution mode, my goal is progress: I get up each day focused on moving one-step closer to my goal. In the past, when I was in this mode, I had a job, I was in school, or I otherwise had something that I was working toward. For example, when I was doing research for my Ph.D., I was 100% in execution mode – I had to publish roughly one first-author paper each year, and that meant careful planning. Sure, there was a lot of brainstorming, experimentation, and learning, but the key task each day was to bring me one step closer to that next paper, and hence, to that next chapter of my dissertation, and ultimately, to graduation. When I was at Google and Amazon, the goals were different and the tasks were different, but the approach was the same: move forward each day and make progress on the goal.

But there is another way to work, which I call exploration mode. In this mode, I get up each day not to make progress toward a goal, but rather, to open new doors and discover things that I hadn’t ever thought about. When I’m in exploration mode, I plan my life around attending local meetups on topics I’m interested in. I travel to attend conferences in areas of science or business that I find interesting. I reach out to old connections from LinkedIn to ask if they would like to grab coffee. I publish articles online. Once, I even flew across the country—from Boston to San Francisco—just to have lunch with an old colleague because I had heard he was building something interesting and I was curious. And because I don’t know exactly where I’m going when I’m in this mode, I optimize my life to be playful and spontaneous. I have faith that something will pop up that might surprise me.

See, the biggest value that you get out of exploring is that you give yourself the potential to uncover the “unknown unknowns”: the stuff you would find interesting that you didn’t ever know to look for. You set your life up for serendipity, not for accomplishment. You recognize that life is often governed more by chance and probability than by planned implementation.

Why is it important to have two modes? Well, it’s because when you’re in execution mode, there’s no time to look for new jobs or to “explore”. Even if you think you’re exploring, you’re still getting up each day with 90% of your attention focused on your immediate bill-paying work. But when you give yourself time to explore, you give yourself the gift of figuring out what you really want. You get off hamster-wheel of jumping from job-to-job focused on opportunity or comfort but knowing deep inside you that you are not doing what you really were meant to be. You step away from fear and step towards the life you really want.

Because it’s impossible for me to fully embrace both execution mode and exploration mode simultaneously, I prefer to alternate between these modes in life—much like how E. coli switches between running and tumbling. Practically, this means that if after several years of focused work, I feel I'm not progressing toward my life goals, I switch to exploration. This usually means leaving my job on good terms and spending several months (or up to a year) exploring what I want to do next. Academics call this a "sabbatical," traditionally a one-year break every seven years. But this approach isn't limited to academia—professionals in business can also benefit from this type of intentional pause and reflection.

Of course, the irony here is that conducting a successful exploration period in life takes serious planning and a financial cushion. The modern world—from rent, to food, to student loans, to healthcare costs, and more—makes this a really, really difficult thing to do. And the reality of financial constraints means that for many people, leaving a steady job just isn't a realistic option – many people just don’t have the savings or resources to quit their jobs cold-turkey. While cutting expenses and building-up one’s savings can be a good start, doing so isn’t often isn't feasible when managing debt, supporting a family, or dealing with essential ongoing costs.[1] I was able to make it work by stripping away all non-essentials, downgrading to a bare-bones apartment, and supplementing my income with occasional consulting projects, but I know that not everyone can.

Note that the benefits of switching to exploration mode may vary depending on one’s career path. Exploration might be less valuable for people who have invested heavily in specialized training (e.g., physicians or airline pilots), then for those in creative fields like filmmaking or entrepreneurship. And of course, if one is already satisfied and fulfilled in one’s current work, there may be no need to seek out new directions at all. However, for those feeling stuck or dissatisfied with their career trajectory, a pause can be worth fighting for. Such a deliberate break can help prevent not just burnout, but the more profound risk of spending years moving towards a destination that doesn't align with one’s true aspirations.

In the end, I’ve discovered that treating my career as a continuous, linear path of constant execution is exhausting and limiting. By always planning and doing, I was only seeing the options I already knew about. It was when I started alternating my career between periods of execution and exploration, similar to how E. coli adapts, that I was able to let go of rigid planning and become more open to unexpected opportunities. I was able to move from someone who was burned out and frustrated to someone who was getting up each day focused on what I wanted to work on - what I was most interested in doing. It’s funny - sometimes even the simplest of creatures in nature inspire solutions to our most complex problems.

[1] While I find that alternating serially between periods of execution and exploration in my career is especially effective, for people who don’t want to leave their current jobs, one approach is to carve out small pockets of time (e.g., one day a week, like a Saturday) where the sole focus is on exploration mode. The key is to intentionally separate the two modes of thought and avoid multitasking. It’s this separation (and the resulting ability to focus) that I have found most useful for opening my mind up to new possibilities.

Great analogy. I too will channel e.coli!

We're built to oscillate between activity and rest, contraction and expansion, why not execution and exploration? I like to think of bacteria as our original ancestors. Following their interest, curiosity and desire, running, tumbling, living, dying, they created our atmosphere and land masses, evolving into creatures who build airplanes to hop continents, eating and pooping, invigorating every ecosystem, unimaginably diverse and creative.